- Home

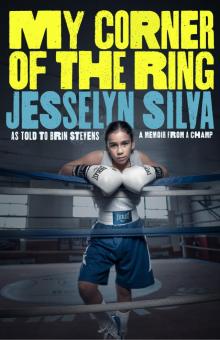

- Jesselyn Silva

My Corner of the Ring Page 2

My Corner of the Ring Read online

Page 2

I came in fast in the second round, and he came in slowly again. Another intimidation tactic I’d learn about later in my boxing career: make them come to you. I threw the first jab, and it was a strike! Right to his jaw. Not hard enough to move him back, but it did startle him. And it felt goooood.

There are two ways to describe how you feel when you’ve given someone a clean uppercut to the jaw: terror and pleasure. I read in school that both feelings live in the same part of your brain. So there I was, caught between pleasure and terror when he hit me with a powerful right-hand pow to the face. He hit me so hard, my head snapped back. A boxer with more experience would have foreseen this or recovered. But I burst into tears and covered my face again. My father was silent. Greg’s mother shrieked and grabbed her cheeks. “Are you ready to quit?!” Paulie yelled. Judging by the terrified look on all their faces, the correct answer would have been yes.

“No!” I heaved through tears. “No!”

“Come on, Jess!” Papi pleaded.

Paulie couldn’t stop me. Papi couldn’t stop me. Greg didn’t want to stop me. Nobody could stop me. We were still fighting when the yellow light came on. Then red. Bell. Round two was over. I had survived two rounds. One more round to go.

In my corner, during the quick thirty-second break, I stared in shock. Papi held my water bottle, my coach held my mouthpiece. They were yelling things to each other, then yelling at each other. And telling me things that didn’t make sense. I thought I was going to hyperventilate.

“Let’s end this at two rounds,” Paulie said.

If I quit after two rounds, it would all be over—and by it, I’m not just talking about my fight with the boy. If I quit now, the whole thing would be over: my chance to get into the ring again, to ever fight in a real sanctioned match, to go even further with this sport that I had quickly grown interested in. I thought about the first time I put on boxing gloves. I remember it gave me an immediate sense of strength that I had never felt before. My love of boxing grew from there as I developed my craft. If I stopped now, I would be ending my chances of being a boxer forever. And no one but me would second-guess it if I never came back to the ring again. Maybe I was crazy to enter the big playground at first, but I was there, and I wasn’t coming there to play.

I saw my idols, giants and legends in my mind, dance with arrogance in the ring. They made it look so easy. But when you’re actually up there staring at a hard fist coming at you, it’s a different story. I still wasn’t ready to quit, though. I didn’t care if I was just a little girl crying in a corner. If that’s how it was going to go down, I figured the worst that could happen would be that I would go down crying. They wouldn’t let me die out there, so I couldn’t quit. I wouldn’t quit. If I quit, I would have learned nothing. And I had more to learn. More to figure out. More punches to give, and fewer punches to take. More crying to do. I knew this was my sport—the one that somehow seemed to be choosing me as much as I was choosing it, and the sport that I wanted to dedicate my life to. People might have thought I was too young at the time to know—“No seven-year-old knows what they want to do with the rest of their life”—but I knew. I had known the second I’d put on the gloves a few months earlier when my father let me try on his. I’d slipped them on and hollered jokingly “I’m queen of the world!” But now I wasn’t joking. The gloves, the ring, the fight, even the fear made me feel bigger than I had ever felt in my entire life. And it was this fear and frustration and rush of adrenaline that had drawn me further in to this crazy world of boxing.

“Jess,” Paulie said to me. “Come on, let’s end this at two . . . call it quits.”

I stared at the center of the ring. I looked around the gym at all the boys and men shadowboxing and punching speed bags. I saw Greg’s mom wearing a pretty outfit with a shiny necklace and high heels, cheering him on from the side. I imagined myself one day standing on the side in a pretty outfit and high heels cheering someone else on, and I thought, No, the center of that ring needs me. I thought of the images we had seen in school of the Romans and Greeks fighting each other. The images were all of men. I thought of the boxing movies and classic boxing matches I’d watched with my father and great-grandfather. All men.

Where were all the girls? Even at seven years old it was pretty clear to me that this was a sport dominated by boys. But at that moment, in the ring, all I wanted to do was prove that a little seven-year-old has a shot at beating a bigger ten-year-old.

Red light. Red light. Red light.

“No, put in my mouthpiece.” I stood up. “I’m not done.” My body wobbled a little as I rose, but I shook it off.

“Oh geez . . . That girl’s got no quit in her!” Papi said. And for the first time that day, he cracked a smile, even chuckled. It was worth the pain to see him proud of me.

“Hey,” one of the boys ringside said, “Jess is going back in!”

“Chica loca!” another boy responded.

More woof-woof boys started to gather around the ring chanting and cheering. Men and boys stopped their training routines to take notice. I couldn’t tell if they were rooting for me or Greg, but it didn’t matter.

My biceps were tight and my right thumb was throbbing and I felt crampy in both calves. Red light, red light, red light. Green . . .

Greg came out with speed this time.

“That’s it, honey!” his mother called from the side. I wasn’t prepared for this. Instinct drove me back to my corner.

The crowd of boys laughed and threw their hands in the air; they expected this from a girl. I looked at my father. He no longer looked worried. He looked angry—not at me, but at a scene that seemed to be so clearly divided between boy versus girl. He said nothing. But our eyes met, and I went back in to meet the boy in the center of the ring. I didn’t think about what was going to happen next. I just knew that I didn’t want to quit. I didn’t need to win. I wasn’t going to win. All I needed to do was stay in the ring one and a half more minutes and finish. I could handle that.

The third round didn’t go well. Greg stopped hitting so hard. But he still threw a lot of jabs. I was worn out from crying, and kept missing punches. The boy got the better of me pretty quickly that last round, and I ended up leaving the ring in tears. (Again!) But I did stay in until the gentle bell rang.

After the fight, Paulie patted me on the head and said, “You got guts, Jess. That’ll take you far in this sport.”

Somehow it didn’t feel reassuring.

* * *

THE FEELING OF mutually agreeing to punch a stranger is weirdly exciting. You know you’re about to start something where at least one of you could get hurt. But it’s not just about the hits. It’s more about pushing past fear. After the fight I lay on the floor of the gym bathroom in complete misery. My ego was hurt more than my body. My skills were clumsy; I wasn’t as experienced at boxing as I wanted to be. My coach, Paulie, had told me what a dynamo I was during training sessions, but out in the ring I had felt naïve and unprepared. And I was embarrassed. I didn’t want to face the people in the gym.

It wasn’t just that Greg was bigger and stronger. It was that I had such a long way to go. I was too slow in my technique and too wild in my mind. I was learning that even if you think you can do something and people have told you you’re pretty good at it, maybe it’s not true. That’s how I was feeling. Not very good. I’d thought that even if I didn’t get a good punch in, at least I’d end the fight feeling tough. But I felt the opposite of tough—it’s hard to feel tough when you leave the ring feeling weak.

I stood up, washed my face, and looked in the mirror. My cheeks were swollen and red, but not from fighting—from crying.

How on earth had I gotten here anyway?

* * *

TWO MONTHS EARLIER, before I ever knew what boxing was, Papi had loaded up my little brother, Jesiah, and me in the car one day after school and told us we were heading

to Edgewater, a few towns over, to do something a little different. My brother was so excited, he ran back into his room and grabbed his binoculars. Edgewater is known for its dramatic undercliffs along the Hudson River and hazy views of the Manhattan skyline. But the coolest thing about Edgewater is its monk parakeets.

Rumor has it that back in the 1960s, a crate from South America full of beautiful small green parrots was damaged while being unloaded from a plane at John F. Kennedy airport. The whole flock of parakeets escaped its intended fate in dreary pet shops throughout New York City, and instead ended up in the trees of Edgewater. No one could figure out how they survived the harsh conditions, but there they remained. All along Memorial Park you could see huge four-foot-tall stick nests where the birds lived. Jesiah, with his binoculars around his neck, and I assumed when Papi said we were heading to Edgewater that he meant to see the parakeets.

Instead, he took us to a boxing gym. The Jim was dark. Dank. Small. Uninviting. Smelled like feet. Full of sweaty men. Jesiah was disappointed and grumpy when we showed up. I wasn’t very interested either, at first. Papi took us to the kids’ corner, gave Jesiah his iPhone, and told him to play a video game while he warmed up in the ring. I pulled out my sketchpad to draw. I loved to draw. It relaxed me and I was always surprised to see what ideas I could bring to life. My father gave me the sketchpad to doodle on when I was bored, but I had started to take the pad with me when we were driving around doing errands or driving to and from school. I looked up at my father, who was now moving around the ring doing simple jabs, and I started to sketch him.

My father had been pretty stressed out, always tired, always worried about work and bills and grown-up stuff and getting us to and from school. A friend had suggested he try boxing to relieve his stress and get some exercise. Jim’s was the only place within a half hour’s drive that allowed kids in the facility while adults trained. So dark, smelly Jim’s it was. The ring wasn’t even in the center of the gym. You’d think in a boxing gym the ring would be at the center, but it kind of seemed like an afterthought in this place.

The first time I saw my father box, it wasn’t beautiful, but it was magical. He was smiling, dancing, light on his feet. And strong. Free and determined. I mean, don’t get me wrong, he was a terrible boxer, but there’s something about a person taking a punch and giving a punch: I swear you see their soul. I swear it. They allow themselves to get beaten down, to experience a sense of defeat in their bodies, but through that, find their strength at the same time. I’d never seen a sport like that before. As I became more familiar with boxing, I started to see something else. All boxing gyms have it—a lavender sort of dust that floats around, like passion, like something big is being released into the air. Like something big is happening inside a person when they fight. It’s about building order and discipline. Your body is telling you to stop, but you can’t, and that builds character. And I wanted it. All of it. This was the kind of playground that made sense to me. I studied every move and countermove, processing every instruction. I was the only kid in the kids’ corner not glued to an iPhone. I was glued to the boxing ring. I decided to ask my dad if I could have a turn out there.

“Hey Papi, can I put on a pair of gloves?”

“Is it cool if she puts on a pair of gloves and hits the bag?” Papi asked Paulie.

“Sure—” Paulie started to say.

But without waiting for an answer, I was up and standing next to my father. I slipped on his loose-fitting gloves and practiced the moves I’d just seen.

“Hey, are you a leftie, Jess?” Paulie asked.

“My whole life,” I responded.

“You’re lucky. You got the southpaw advantage.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Here. Let me show you.” Paulie bent down a little into a stance.

“See, most fighters are righties, so they lead with their right hand. Your strength is in your left side. So look, you have a left stance like this. Your right foot is your front foot, and your left foot is back, like this.” He showed me, then continued, “Your right hand is your jab hand, your left hand is your power hand. That’s a pretty good advantage if you’re a boxer because most opponents won’t be used to a power hit coming from the left. Get it?” I nodded, then paused. “What if you’re a rightie?” I asked.

“If you’re a rightie, you usually have an orthodox stance. Like this.” Then he showed me what that looked like.

“But here, let me see you stand in a southpaw stance.”

I caught on right away.

“Good!” Paulie said. “Now let me see you throw a punch.” And with that, I landed a solid straight left punch in his gut.

I guess I was pretty good, because both my father and Paulie looked at each other in surprise.

That was the day I became a boxer.

CHAPTER TWO

A DIFFERENT KIND OF FIGHT

People asked me where I got my fighting spirit, and I would tell them it runs in the family.

Some people say every boxer has a story about struggle that brought them to the ring in the first place. I think the struggle came generations before me.

My grandparents on both sides were immigrants. My father was named after his father, Pedro, who was named after his father, Pedro, and his father, Pedro. My brother’s a Pedro, but he goes by his middle name, Jesiah. There are a lot of Pedros in my family. I’m one of the few girls in the family, and the only Jesselyn. My grandmother joked that our ancestors were good at making boys but bad at raising them.

Papi’s father, my grandfather, came over on a packed lobster boat from the port of Mariel, Cuba, in 1980 when he was twenty years old. He couldn’t stand the smell of shellfish after that. I never actually met him before he died, but I’ve always felt like I understood his fight to get to America and his struggle in America.

Like many Cubans coming to the United States at that time, my grandfather sought freedom from the powerful rulers of his country. Visions of the American dream drew him to this land. But his overseas trip here wasn’t easy. The ocean was rough, the skies were dark, and the small fishing boat was so weighed down with people that every wave crashed hard on top of its passengers, leaving them wet, dehydrated, and afraid. Fearing the vast sea surrounding them, my grandfather once told my father, was a blessing in disguise, because it made them forget about their hungry bellies and various sicknesses, and the horrible filth and stench inside the vessel. He said he was one of the lucky ones. That on more than one occasion they passed travelers in rafts as small as five feet long with nothing more than a bottle of rum and a bucket of water.

Once their fishing boat hit the Florida Straits, sharks started to appear, looking for people to grab off flimsy boats. He said it wasn’t a shock when passengers saw a human leg float past. Their trip took fifteen hours, but in that time people on the boat had already started to hallucinate—probably because of a combination of dehydration and hypothermia.

When my weary grandfather landed in Florida, he approached a young Hispanic man sitting on the dock and asked him in Spanish, “Where are we?” The young man handed him a Dr Pepper and said in perfect English, “Welcome to the United States of America!” That was the first time my grandfather realized how hard it was going to be to live in a country where he didn’t speak, read, or write the language. I often wondered what it would have been like to be my grandfather. When someone asked him a direct question, he would smile and nod and not be able to answer because he didn’t understand. He was forced to speak in one-word sentences—“Yes” or “No”—when he couldn’t follow along.

My grandfather’s first job was driving a taxi for Good Cab in Union City, New Jersey.

“Always respect the customers,” his boss would say to him in Spanish. “Always be polite, even if the customer doesn’t tip. And always, always drive safely! One car accident and you’re fired.”

Good Cab was whe

re my grandfather met my grandmother. She was the beautiful dispatcher at the cab company and had arrived in the United States from Ecuador a few years earlier with a similar story of leaving the familiarities of home and leaving loved ones behind to start a new life in an unfamiliar land, except instead of traveling by boat, she had landed in New York by airplane. In one hand she had a suitcase, in the other were her tattered identification papers, and in her belly was a growing baby. She was sixteen years old and found herself standing on the sidewalk of the terminal with no one to pick her up and nowhere to go. Tears streamed down her face, and she wondered if she’d made a terrible mistake by leaving her family in hopes of a new life for herself and her future son.

My grandfather and grandmother had a lot in common: they both felt lost, struggling to make it in a strange new land, both trying to better their lives.

They became a couple soon after they met. And then things happened quickly. My father, my grandmother’s second son, was born within a year, and eleven months later my father’s brother Samuel was born. With three young boys and not much money, the American dream felt more like a nightmare. The stress of having little money and living in a cramped apartment caused a lot of worry.

When I asked my father what his father was like, he simply said, “I don’t remember much about him. He wasn’t around a lot.”

Later I found out that my grandfather left his job as a taxi driver and turned to a life of crime—or as my grandmother called it “the underworld jobs.” His underworld job was to steal things and sell them on the street. He ended up in jail many times. To my father, his father was always in and out of his life—one month showering him with attention, another month just gone.

When Papi was seven years old, he developed asthma. On more than one occasion, something affected his lungs, and his mother had to take him to an asthma specialist quite a few times. Then came the medication: inhalers and nasal sprays, both of which he hated to take. Nothing seemed to help him, but eventually he learned to cope with it.

My Corner of the Ring

My Corner of the Ring